Pangborn 2025: Sensory Science in Full Spectrum

Is that wine tasting and color wheels during a workshop? Yes, please!

I landed at this year’s Pangborn Sensory Conference in Philadelphia still buzzing from the International Society of Neurogastronomy Symposium just days before. My own closing talk there, the “Cookie Stomach Theory”, had me on a high of inspiration and camaraderie. So walking into Pangborn, I was already energized and ready to dive into a different but overlapping community of sensory scientists.

A Playful Kickoff

The tone of the meeting was set immediately by co-chairs Helene Hopfer (Penn State), Curtis Luckett (Ingredion), and Alissa Nolden (UMass Amherst), joined by John Hayes (Penn State) in full Philadelphia tuxedo alongside a cameo from Ben Franklin himself. A perfect reminder that science conferences don’t need to be all business, they can embrace playfulness and context too.

I was super excited for this meeting since it’s sorta in my backyard (I live in the Philly suburbs). But also because I got to be part of the organizing committee. I wrote one of the supporting letters to bring Pangborn to Philly and also co-led a networking primer with Emma Feeney before the conference.

Ben Franklin tells us about our founding fathers’ love of tofu…

Sensory Through New Lenses

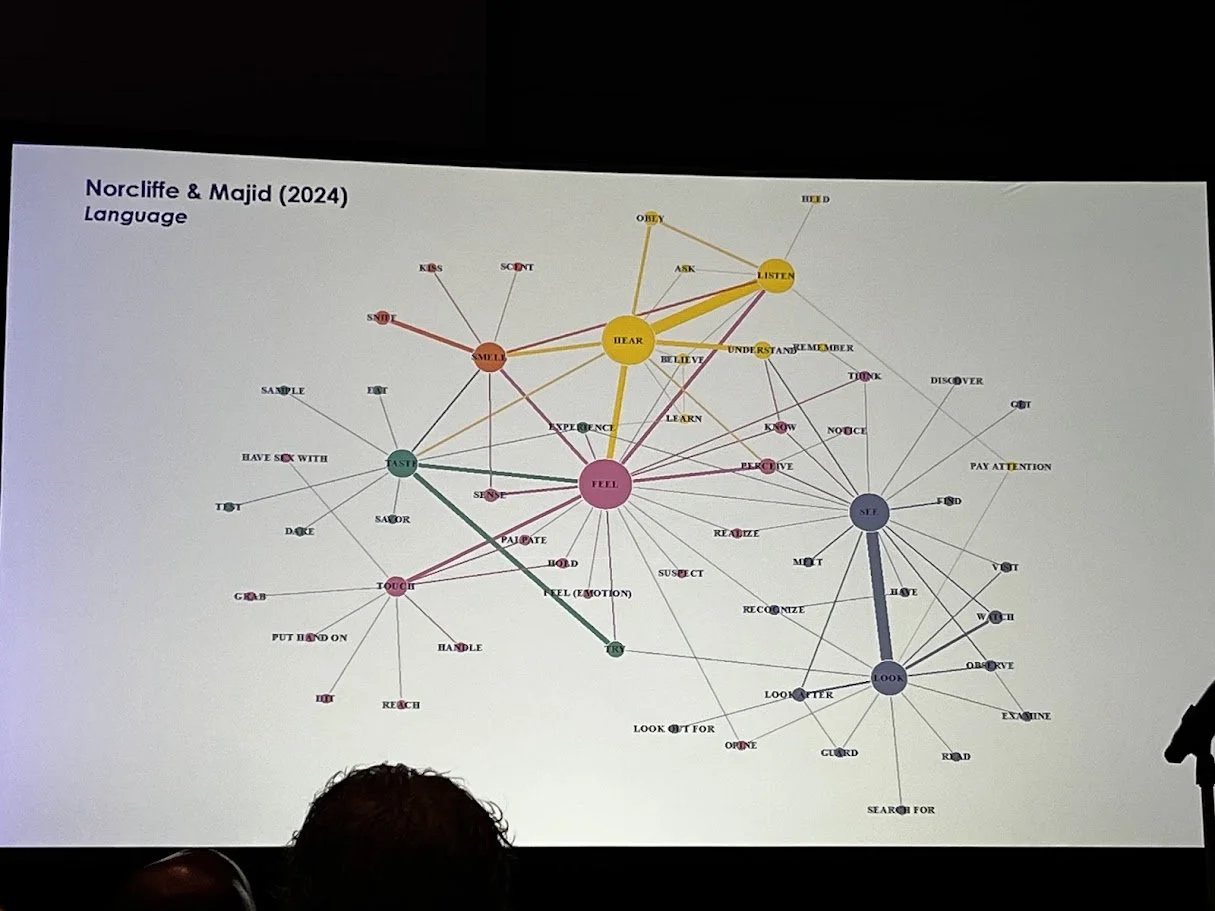

The opening session, “Sensory through the Unconventional Lens,” was a standout. Asifa Majid (Oxford) took us on a global journey asking: are there sensory universals?

Her talk underscored how much of our evidence base is WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies. That bias shapes what we call “fundamental” truths about perception.

What fascinated me most was her discussion of language. Some languages encode olfaction richly, while others struggle. This linguistic scaffolding could partly explain why cross-cultural studies, like the one I did with Valentina Parma to replicate Hertz & Bajec’s work, show different rankings of sensory importance across countries. In their study, Herz and Bajec compared how people value their sense of smell relative to vision and hearing, framing choices between senses and everyday entities like phones, pets, or even their "little left toe." They found that smell is consistently rated as far less valuable than the other senses and, for some (like college students), even less valuable than a phone or hair. Valentina and I were interested in replicating this on a global scale, could these preferences differ across cultures? If a culture’s language gives people the tools to describe smell, perhaps that culture is also more likely to value it.

This connection between linguistic accessibility and sensory salience feels like fertile ground for future research and a reminder that studying perception means grappling not only with biology, but also with culture and communication.

Are some senses easier to talk about than others?

Talking About Emotions

Emotions were a major thread this year (as with SSP last year), and I had the chance to showcase some of my own work. One highlight was a talk I co-presented with Richard Popper (P&K) and Rachel Czapla (RIWI), comparing Explicit CATA and Implicit IAT measures on consumer perceptions of lip products.

Why This Comparison?

Explicit CATA (Check-All-That-Apply): Participants consciously select words that describe a product. It’s quick, transparent, and familiar to sensory researchers.

Implicit IAT (Implicit Association Test): A reaction-time method that captures automatic associations. Instead of asking consumers to check boxes, it measures how quickly they pair product types (matte, gloss, balm) with attributes (e.g., sexy, fun, natural, bold).

We wanted to see whether explicit vs. implicit methods told the same story, or whether they revealed different layers of consumer experience or possibly cognitive strategy.

What We Found

CATA picked up more product differences. Consumers readily applied conscious descriptors: matte = “bold,” gloss = “fun,” balm = “natural.”

IAT was more selective. Only the strongest and most ingrained associations surfaced, those that likely matter most for brand positioning and emotional resonance.

In other words: CATA reflects what people can articulate; IAT reveals what they feel even if they can’t put it into words.

This aligns with dual-process thinking in psychology: reflective vs. intuitive systems. Explicit methods give breadth; implicit methods give depth.

Why It Matters

For product teams, this isn’t an either/or decision:

Explicit methods help optimize and fine-tune when you already know your target attributes.

Implicit methods help answer the deeper question: does the product feel right at a gut level?

Our conclusion: use them together. One maps the conscious landscape, the other uncovers hidden terrain.

From Talk to Workshop

This theme carried directly into the workshop I co-chaired with Richard Popper: “A Skeptic’s Guide to Emotions Research.”

We brought together end-clients (PepsiCo, L’Oréal, Nestlé Health, General Mills, Altria, Mars Wrigley) to share their experiences with emotion measures. Through live polls, we saw the same tension play out:

Most people default to self-report.

Fewer have tried implicit tools like IAT than we anticipated (surprisingly close in usage to facial coding).

Researchers are split on whether emotion data is more trustworthy than liking scores with many saying it depends.

And while everyone talks about validation, few have a clear roadmap for how to do it.

When asked about future tools, interest skewed toward implicit methods and multi-method approaches, with very little appetite for high-tech EEG or fMRI.

In short: the same head vs. heart dynamic I presented in the talk reappeared in the workshop discussion. Explicit approaches dominate because they’re easy and interpretable. Implicit methods intrigue people but remain underused, partly because they’re harder to validate and explain and are less understood.

My takeaway across both sessions: the answer isn’t one method, it’s multimodal. Different tools reveal different sides of the consumer. And to really understand emotion, we need to embrace that complexity rather than search for a single silver bullet.

Two emotions presentations from yours truly!

Bad Science in Bright Lights

These debates echoed on the poster floor, where too many presentations equated physiology with emotion. One striking case involved a presenter convinced, thanks to her vendor, that heart rate is emotion.

The scientific problem is clear: physiological changes are multiply determined. A product stimulus that increases heart rate could be acting pharmacologically (like caffeine), environmentally (like temperature), or emotionally. Without careful controls, attributing HR changes to emotion is methodological overreach. Even HRV, which can hint at sympathetic vs. parasympathetic balance, is not a direct readout of emotional state.

This overclaiming is what gives “neuro” and “biometric” methods a bad reputation. And it reflects a bigger systemic issue: vendors selling black-box metrics, while researchers using them often lack the expertise to interrogate the methods. As someone who’s been both a vendor and a critic, I’m painfully aware of how tempting it is to market simple stories from messy data. But the science demands nuance.

Holly and I take a critical eye to the posters…

Recognition & Community

Thankfully, the conference also reminded me of the joy in this community. Riding up the escalator, someone spotted me and shouted “Nerdo!” A small moment, but meaningful, proof that embracing my nerd identity resonates.

And in every hallway, I found conversations with colleagues, friends, and clients. That mix of reunion and idea exchange is the real heartbeat of Pangborn.

Is there a nerdo in the house????

AI Everywhere (But Not Always New)

AI dominated the program. Honestly, I joke now: is it even a conference if it doesn’t mention AI? At Pangborn, many talks boiled down to chatbot-style surveys—useful, but not revolutionary.

Greg Stucky (Insights Now) framed this as a transition from digital revolution to cognitive revolution, emphasizing AI as a new gateway to the “voice of the consumer.” I appreciated his articulation, and his discussion of their Habit Flywheel sparked some interesting hallway debates.

In my original write-up, I compared it to Duhigg’s Habit Loop. Greg rightly pointed out that their framework predates Duhigg’s work, and that Duhigg himself drew on earlier models (like Neale Martin’s Habit from 2008). More importantly, Insights Now’s flywheel is tailored for CPG innovation, focusing on how sensory cues and contexts shape consumer product habits. That’s a very different intent from Duhigg’s focus on personal habit change. So thank you Greg for pointing this out and for reading!

Frameworks like these raise important insights as well as questions. They’re useful organizing tools: easy to communicate, easy to remember. But by design, they can also simplify messy human behavior into clean loops. That can make them powerful for client conversations and organizing insights, but that can also risk glossing over complexity or overpromising predictability.

The takeaway for me: frameworks can be great thinking tools, but they’re not magic bullets. The value lies in applying them transparently and in the right context, not in treating them as one-size-fits-all answers. And AI and LLMs may present a really interesting avenue for this line of thinking.

GLP-1s: The Next Big Variable

Another major theme was GLP-1 medications (e.g., semaglutide). RAND recently reported that nearly 12% of Americans have used them, a staggering figure with direct implications for consumer behavior.

These drugs don’t just alter appetite; they may reshape perception itself. Colleagues pointed out impacts on flavor, texture sensitivity, and even product appeal. Nina from L’Oréal shared preliminary observations suggesting effects on skin and hair biology as well. That floored me.

We’re entering uncharted territory where a large consumer segment may literally experience the world differently because of pharmacological modulation. This will have ripple effects across food, beverage, beauty, and beyond. The sensory science community cannot afford to treat GLP-1s as a niche variable, they are becoming a mainstream factor in product design and testing.

Beyond Food: A Broader Sensory Landscape

It was refreshing to see sensory science represented outside of food. L’Oréal’s interactive booth showcased multisensory consumer experiences, reinforcing that sensory perception isn't just about taste, it’s about the whole embodied interaction with products.

Monell Chemical Senses Center, proudly in its home city, hosted its biggest-ever open house. Lab tours, meet-and-greets, and the launch of the new Monell Alumni Association (which I’m chairing) made it a milestone moment. From MSAP students to legends like Harry Lawless, the alumni gathering embodied Monell’s spirit: once a Monellian, always a Monellian.

Monell may be all about sensory science, but Monellians are about fun, right?

Dancing It Out

And of course, no Pangborn is complete without the gala. This year we took over Reading Terminal Market, eating, drinking, and dancing late into the night. My knees still haven’t forgiven me.

The Gala is always a dancing delight. I love how everyone really gets into it!

Looking Ahead

Pangborn 2025 was both exhausting and energizing. It showed sensory science at its best, probing perception, grappling with emotion, embracing new tools while also revealing where we must be vigilant: avoiding overclaim, validating methods, and resisting the lure of shiny-but-shallow solutions.

I left with new ideas, renewed connections, and yes, sore legs from dancing.

Hit me up if you’d like to hear some stories about the gala 😉💃🏽

See you in Mérida, Mexico in 2027!